Lately, I don’t seem to be getting nearly as agitated about political stuff. Nor have I been writing about it much. Maybe I’m just exhausted.

But there’s one assertion that I hear over and over again that automatically heats up my blood. It basically goes like this: “They all suck! They’re just terrible. All they care about are themselves and making money. Every damn one of them. All politicians are exactly the same.”

Most of the time I let it go. It’s just too ignorant and simplistic an opinion to really get into — and that’s assuming that the other person is really listening.

But today I can’t stop thinking about it. And that’s because my friend Adlai Stevenson III — a man whose entire life shoots down that cynical assertion in a heartbeat — has just passed away at the age of 90.

Adlai was born and raised smack-dab in the middle of the largest multi-generational political shadow one can imagine: A father who was Illinois Governor and twice nominated by his party to run for the presidency. A grandfather who was Illinois Secretary of State. A great-grandfather who was Vice President of the United States. And a great-great-grandfather, Jesse Fell, who persuaded Abraham Lincoln to run for president and proposed the historic Lincoln-Douglas debates. Adlai III knew at a young age just how intimidating a lineage he was preceded by. But it only made his choice clearer. He once explained to me that he knew full well it was his destiny: “I was born with an incurable hereditary case of politics.”

What Adlai truly loved about politics was achieving victories that would actually make things better. Not just in Americans’ lives and their country’s stature in the world — but also the political process itself. He viewed politics as public service, plain and simple. And his life’s journey reflected this philosophy at every turn.

Adlai Ewing Stevenson III was born on October 10, 1930, in Chicago. He graduated Harvard College in 1952 and then joined the U.S. Marines, serving in a tank unit in Korea. He married Nancy Anderson soon after and then earned a law degree from Harvard Law School.

Adlai would go on to serve as an Illinois State Representative, State Treasurer and as a member of the U.S. Senate for more than a decade. But it wasn’t the political titles that mattered to him. It’s what he could DO with them.

In the Illinois General Assembly, Adlai sponsored more than 80 bills in his lone two-year term, including legislation to rein in lobbying and conflicts of interest in government. For his efforts, he was named “best legislator” by the Independent Voters of Illinois.

As State Treasurer, he ramped up the powers of the office to make things happen. He quadrupled the earnings on investment of state funds while consistently cutting the annual budget. Adlai got rid of state patronage, pulled state funds from banks that were engaged in racial discrimination, and placed money in minority-owned banks to finance urban development, small business creation and low-income housing.

In the U.S. Senate, Adlai continued his crusade to make integrity in government a reality.

Nearly a year before Nixon was forced to resign, Adlai spoke up forcefully about the Watergate scandal:

“All of us — Republicans and Democrats — have an interest in clearing the record. The faith of the people in their system and their leaders — a faith that has already been shaken enough — is at stake.”

Adlai was a leader on myriad national and international issues as a member of the Senate. But true to his character, he made reform the priority. He served as the first-ever Chairman of the Senate Ethics Committee and led the “first major reorganization of the Senate” since the committee system was first formed in the early 1800s.

That “reorganization” may sound egg-heady, but it helped our government to operate more effectively. This was during a time where the Senate was not a total joke. In an interview I did with Adlai a few years ago, he described that period of time:

“It kind of hurts me to see this because I love the old Senate. It really worked. There wasn’t this kind of partisanship. We crossed the aisle. We tried to support our president, no matter the party. And cloture, the filibuster that gave the minority an opportunity to be heard. We protected the minority. But when they’d had that opportunity, an ample opportunity, then we cut off the debate and passed legislation by 51 votes.”

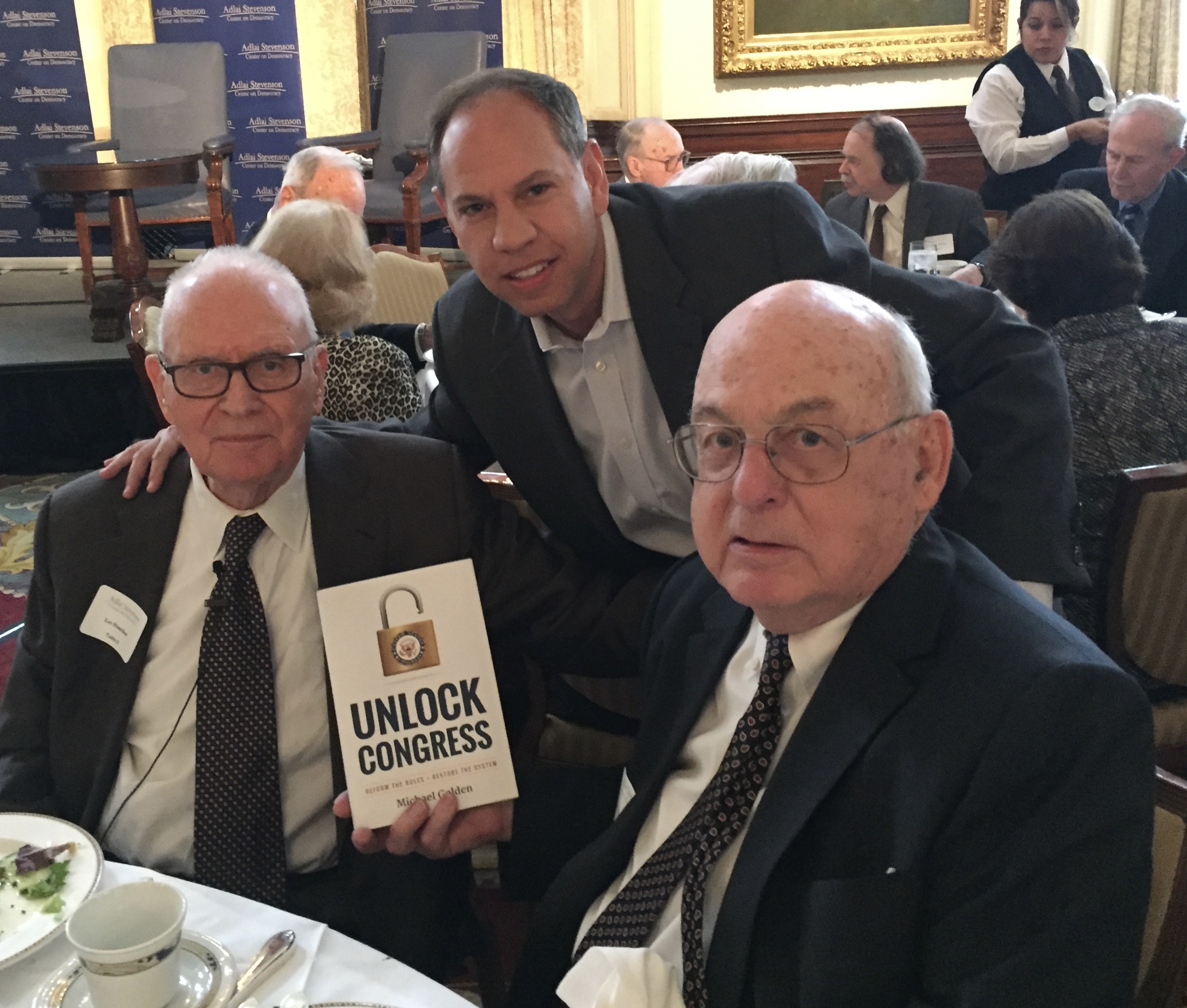

I first met Adlai Stevenson III at an event that his Stevenson Center for Democracy was hosting at the Union League Club of Chicago. There, I introduced myself to him and former Congressman Lee Hamilton (D-IN) — and gave them both a copy of my book Unlock Congress.

To my shock and elation, the Senator called me a month later and said he wanted my help. At the age of 87, Adlai was creating an Agenda for Political Reform — and he wanted me to write the portion that addressed how new rules could transform the U.S. Congress. Of course, I said yes, and a few weeks later the Stevenson Center named me as a Senior Fellow on government reform.

That phone call with Adlai was the beginning of a friendship with him and his wife Nancy that brought an immense amount of joy and wisdom into my life. More than they have any idea.

Over the next three years, in his late 80’s and with health challenges, I watched Adlai put together a national coalition of reform organizations to support his agenda. He did it with more piss and vinegar than any colleague I know in my own age cohort. He was tough. He pushed everyone. And everyone knew that he believed in every single word that he wrote and spoke. Adlai described the effort as a guest on my podcast:

“I think the time is ripe. We put together a really comprehensive, sensible, agenda, though not everybody can expect it to agree on every little particular. Maybe we’ve also put together a platform that candidates can run on and support and the people can support to bring about real change. And by that, I mean, change that restores government to the people but also restores our values as Americans to our politics. I’m confident we can do it.”

Adlai brought national reform luminaries to the table; folks like Norman Ornstein and Trevor Potter and organizations like Common Cause and Issue One. While the coalition has not yet turned into a broad electoral movement, our work was the seed that birthed a new government reform publication called The Fulcrum. We all knew that education was the first step in the journey to motivate the nation to structurally change our political system. So we took that first step.

Adlai Stevenson III died from Lewy body disease and dementia on Monday, September 6. To me, the size of his loss falls into the category of immeasurable.

The one comfort about Ad’s passing is that he was at home and surrounded by his beloved family during his final days and hours. As I conveyed my sadness to Nancy over the phone, she projected gratitude and strength. It is the Stevenson way.

Nancy also said that as hard as it is for the family right now, it is important that Adlai is finally at peace. A great man, never to be forgotten.

Also one damn righteous politician. They exist.