(Excerpt from Chapter 5 of Unlock Congress: THE PROBLEM)

The lead-off defect in the D.C. 4-3 is the power of the almighty political dollar. In the New Testament, the Apostle Paul described money as “a root to all kinds of evil.” In the campaign world, it is often referred to as “the mother’s milk of politics.” While the other three defects are harmful to either the House or the Senate alone, the money flood lays its greedy hands on every single one of our 535 members in Congress.

A trip back to the big screen starts us off here. In the 1998 political comedy Bulworth, U.S. Senator Jay Bulworth mistakenly believes he has a serious disease that will soon cut his life short. Much like that criminal suspect who has been granted immunity, the senator now feels free to speak the truth in his re-election bid without worrying about the consequences. So when he’s asked at a large church meeting why he hasn’t supported a bill that would help working folks to obtain fire and life insurance, he shocks the crowd with a deadpan display of raw honesty:

“Well, ’cause you really haven’t contributed any money to my campaign, have you? You got any idea how much these insurance companies come up with? They pretty much depend on me to get a bill like that and bottle it up in my committee during an election. And in that way we can kill it while you’re not looking.”

Now here’s the not-so-secret, dirty little secret: that’s how it really works. Campaign donors and special interests give gobs of money to members of Congress—and they expect results. Jack Abramoff was one of the most powerful lobbyists in our nation’s capital for decades, before he was convicted and sentenced to six years in federal prison for bribing public officials. In 2011, after his release, “Casino Jack” was asked if it was easy to get what he wanted from lawmakers. He responded,

“I think people are under the impression that the corruption only involves somebody handing over a check and getting a favor. And that’s not the case. The corruption, the bribery, call it, because ultimately that’s what it is—that’s what the whole system is … I’m talking about giving a gift to somebody who makes a decision on behalf of the public. At the end of the day, that’s really what bribery is. But it is done every day and it is still being done. The truth is there were very few members who I could even name or could think of who didn’t at some level participate in that.”

But incredibly, most of this money dance is legal. Through laws passed by Congress (and occasionally ruled on by the Supreme Court), the system is intentionally set up to allow a slew of funds to keep rolling in. Incumbents need the dough to keep their feet on that spinning re-election wheel. The rules are rife with loopholes, and as long as legislators, campaign donors, and lobbyists don’t flagrantly break the law and get caught for clearly expressed quid pro quos (as Abramoff did), just about anything goes. In every election cycle, the cash count climbs.

Let’s start with campaign spending. In 2004, a Washington Post headline declared: “Cost of Congressional Campaign Skyrockets,” estimating a new record average of more than $1 million to win a seat in the House—double the $500,000 it had cost a decade earlier. In 2012, just eight years later, CNN offered this headline: “Cost to Win Congressional Election Skyrockets.” Sound familiar? Only now the price tag was $1.6 million—50 percent higher than 2004 and more than four times what a House seat cost in 1986. And the average toll required to get elected to the U.S. Senate in 2012 eclipsed $10 million for the first time ever. In 2014, a North Carolina Senate contest set a new high for a single race—more than $113 million was spent. None of these records stand for very long.

When we extrapolate these numbers into national totals and compare them to years past, the incline is eye-popping. Back in 1974, the total money raised and spent by all House and Senate campaigns was $77 million. In 2012, that figure was more than $1.8 billion.7 On top of those dollars collected by the campaigns, political action committees (PACs) spent more than $400 million in 2012 to express their preferences—a far cry from the $34 million that PACs contributed back in 1978. And then we have the millions of dollars that the two national political parties reel in and then shell back out to members. All legal.

And there’s more. Much more. Lobbying money. Special interests throw in huge sums of cash to their lobbyists to purchase access to lawmakers. The official total spent on lobbying in 2013 was $3.2 billion. This figure is “official” because it is tracked through the 12,281 lobbyists who are officially “registered.” The catch? Not all lobbyists are registered. Some self-classify themselves as “strategic advisors” or “historians,” and there is no penalty for evading registration. American University professor James Thurber has been studying lobbying since the 1980s. He estimates that the real number of lobbyists is more like 100,000—and that they generate closer to $9 billion.

All of this lobbyist cash is doled out strategically. Return on investment is the goal. A 2009 report in the American Journal of Political Science revealed that for every $1 that a lobbying firm injects into the system on tax policy, the benefit to the clients ranges from $6 to $20.

The lobbying tango continues for many members of Congress when it is time to launch their next career: lobbyist. Between 1998 and 2004, 43 percent of U.S. senators and representatives who left office slid into positions at lobbying firms—a 40 percent jump since 1973. Connections and relationships are financially valuable in Washington, D.C.—for the lobbyists who give the money, and especially for former members of

Congress whose pathways back into the corridors of power are even more direct. U.S. Representative Jim Cooper (D-TN) says it best: “Capitol Hill is a farm league for K Street.”

The accelerated pace of the money chase in Congress did not happen by accident. It started in the 1970s when the rise of television advertising enabled politicians to cut through the clutter and speak directly to voters in strategically created thirty-second spots. Armed with polling data, congressional candidates and their hired-gun consultants could now craft ad messages tailored to specific voting blocs. The race was on to raise more dollars than your opponent—in primaries and general elections—so that you could buy the highest number of gross ratings points on TV and drown out the voice of your competitors. The speed setting on the greasy wheel had been shifted up a notch.

Then the “Gingrich Revolution” pushed it to the next level. In his successful effort to win the Republican House majority in 1994 and during the years that ensued, Newt Gingrich changed the game by pressuring his members to raise money not just for their own campaigns, but also for their party. This was the beginning of a new era that saw a heightened urgency for both Democrats and Republicans to pull in even more money to help colleagues of the same political stripe win races. In the 2014 cycle, Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-OH) and Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) each helped to raise over $100 million on behalf of their respective party committees and candidates. Former U.S. Rep. Mickey Edwards (R-OK) watched the escalation from the inside, and he says that beyond the increased time suck, there was another ugly consequence:

“To meet these demands, and to increase their chances of gaining a committee chairmanship or a leadership position within the party, members began to exert fund-raising pressure of their own, leaning hard on those members of the business and professional community whose profitability could be seriously affected by the passage or the non-passage of specific legislation.”

This pressure gets ratcheted up election after election, so much so that now the national parties primarily judge the viability of their own new candidates for Congress based on how much money they can raise. If the challengers are not deemed to be financially competitive, the parties will not open up the cash spigot.

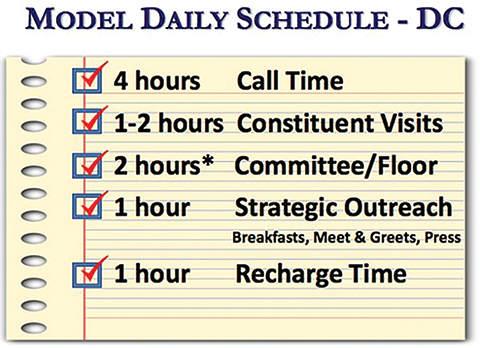

And once new members do get elected, the parties crystallize the money priority more formally. On November 16, 2012, a week after election day, freshman Democrats arriving at their D.C. orientation received a very clear message. A PowerPoint presentation (shown below in Figure 5.1, obtained by Huffington Post) instructed members to make sure they were on the phones asking for money at least four hours a day. If twenty hours per week seems like a lot, keep in mind that such a figure is a recommended minimum, and many members are compelled to spend up to forty to fifty weekly hours on the money hunt. After floor votes on Capitol Hill, representatives can often be seen scurrying off to their party headquarters to start the dialing. Then members are expected to transfer tens of thousands of dollars back to the parties. This is how you move up the committee ranks to amass more power. The wheels keep spinning.

Figure 5.1. Model Daily Schedule While in Washington, D.C.

In Federalist 57, published in 1788, James Madison wrote: “The House of Representatives is so constituted as to support in the members a habitual recollection of their dependence on the people.” A strong tie to citizens is one of the cornerstones of our system. But when the bulk of the money flooding into our nation’s capital comes from the thin slice of folks who can afford to give it, that sacred democratic principle of “dependence on the people” gets violated in breathtaking fashion.

Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Lessig, a campaign finance reform activist and author of the comprehensive book Republic Lost, calls the moneyed climate in Washington a “gift economy.” He explains that the rules in our system allow for all kinds of shadowy, indirect exchanges that put members of Congress in the position of being dependent on the money, as opposed to the American people:

“To see this, think again about the dynamic of this platform: the crucial agent in the middle, the lobbyists, feed a gift economy with members of Congress. No one need intend anything illegal for this economy to flourish. Each side subsidizes the work of the other (lobbyists by securing funds to members; members by securing significant benefits to the clients of the lobbyists). But that subsidy can happen without anyone intending anything in exchange—directly. ‘The system’ permits these gifts, so long as they are not directly exchanged. People working within this system can thus believe—and do believe—that they’re doing nothing wrong by going along with how things work.”

Thus does Congress operate. Whether it’s campaign cash or lobbyist money or a mix of both, the “gift economy” distorts the system. The players who want political favors know they had better write checks big enough to be top of mind—or else. Here’s how former Shell Oil President John Hofmeister describes the corruption:

“There’s a huge price to not paying the price of the campaign request. There’s a price in terms of access. There’s a price in terms of interest by the member. So if you haven’t paid your price of entry, who are you? I’ve actually been asked by a member, ‘Who are you? Because I’ve never met you before. And now that the election’s over you’re coming to ask me for something? Where were you before the election?’… It’s pay to play, and I agree with the word extortion, as harsh a word as that is, it’s an atrocity, that no one seems to care about, because it goes on and goes on and goes on.”

So we can begin to see how this first problem in the D.C. 4-3 skews the system and violates the original spirit of representative democracy outlined in our Constitution. In the next chapter we will examine specific examples of how big money drives counterproductive policy and how it deters other kinds of solutions that Americans say they want. But first, Martin Gilens, professor of politics at Princeton University, gives us an excellent bird’s-eye view of the landscape.

In 2004, Gilens published a study on democratic responsiveness that looked at the relationship between income levels and the public policy proposals Americans want to see passed into law. Gilens analyzed 1,779 questions based on possible policy solutions in the U.S. between 1981 and 2002. Overall, Gilens found “that when Americans with different income levels differ in their policy preferences, actual policy outcomes strongly reflect the preferences of the most affluent but bear virtually no relationship to the preferences of poor or middle-income Americans.”

Specifically, Gilens found that when 90 percent of poor folks were in favor of a policy change, it would be no more likely to become law than if 10 percent of them favored it. Conversely, when wealthy Americans’ expressed their preference for a policy change, it was nearly three times as likely to happen as if they were against it. Finally, when middle-income people were strongly in favor of a proposed policy, it made virtually no difference in the likelihood of its passage.

Ten years later, Gilens and Northwestern University Professor Benjamin Page published another study with even starker conclusions on the power of money. Using a single statistical model to analyze those 1,779 policy issues, they found that the average American truly gets the crumbs. The policy preferences of “economic elites”—defined as Americans in the 90th income percentile—were fifteen times as important in determining policy outcomes versus what ordinary folks wanted. Gilens and Page deliver this upshot:

“In the United States, our findings indicate, the majority does not rule—at least not in the causal sense of actually determining policy outcomes. When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the U.S. political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it.”

It’s a staggering conclusion, especially considering the millions of Americans who have fought and sacrificed for the right to be heard through the power of the democratic vote. Of course, Congress will sometimes need to make unpopular decisions that do not track directly with the voice of the people. In fact, the possibility of their doing so is an important feature of our form of government. But Gilens’s conclusion—the majority does not rule; economic elites do—tells us all we need to know about how money pollutes and distorts the system.

And it gets worse. In 2010, the “Super PAC” was born—injecting yet another money malignancy into the system. That year, two court rulings, including the Supreme Court case Citizens United v. FEC, permitted Super PACs to raise and spend unlimited sums of cash contributed by corporations, unions and individuals. Hundreds of millions of dollars get spent by these groups on campaign communications. These independent expenditures, also known as “IE’s,” are messages that advocate for or against a candidate but may not be coordinated with any candidate or related campaign committee. In the Citizens United decision, a 5- 4 majority on the Court basically deemed corporations as having the same free speech rights as people when it comes to political campaign activity.

Gigantic amounts of Super PAC money further drown out the voices of the majority, if we apply Gilens’s research. A weighty 80 percent of Americans disagreed with the Court’s decision, including one of America’s foremost congressional experts, Norman Ornstein. A scholar at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, Ornstein calls the Citizens United case the most destructive decision he has seen from the Court in decades. Ornstein believes the activity is nothing short of corruption and describes what it means for federal candidates:

“Some alien predator group, and you don’t even know who they are, parachutes in behind your lines, roadblocks all the television time with twenty million dollars to destroy you. So you better go out and raise twenty million dollars in advance for insurance against that happening, or you find your own sugar daddy, which means more interests coming in. And when you’re going out to raise that money, you do one of two things. You give something for it, or you shake somebody down.”

Aggravating this problem even further, we now have the danger of so-called “dark money.” The system now permits groups to register as 501(c)(4) “social welfare” organizations that can raise huge sums of money to spend on independent campaign communications. Why is the money dark? Because under the U.S. tax code and recent interpretations by the courts, such groups have not been required to fully disclose their donors. So not only have outside groups gained outsized power in the process—but we also don’t know where a lot of this influence is coming from.

The danger to our democracy flowing from dark money became highly transparent in the 2014 cycle. Although the total amount of money spent on 2014 congressional elections was higher than the $3.6 billion in the previous midterms, the campaigns themselves actually raised less ($1.5 billion down from $1.8 billion). That decrease was overcome, however, by increases in money from undisclosed donors, partially disclosed donors, and PACs. And of the total broadcast advertising dollars spent in the cycle, 55 percent of it came from undisclosed sources.

As we will see in the next chapter, this organizational money that floods into the system can drive irresponsible performance on some issues while freezing potential progress on others. U.S. Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) explains:

“There’s an entire industry in Washington that makes money on conflict. Some of these outside groups—you know, your Club for Growth types, and your Heritage Action, and your FreedomWorks—they go out and they fundraise by saying that Republicans aren’t sufficiently conservative. Or they pick an issue to go to war on because they can stir the base and raise money on it and pay their big salaries. And what that does in the long run is it takes what would be a solid Republican agenda and causes chaos.”

It’s an expensive obstacle course for members of Congress—a “gift economy” of unconcealed winks, back slaps, and favors galore. The money flood not only damages legislative policy, which we will examine in the next chapter, it also intensifies its sibling defects in the D.C. 4-3. It takes a lot of coin to be clearly heard blasting one’s political opponent in an election campaign. And as soon as the winners arrive in Washington they must immediately begin navigating the pressures of re-election— which starts with the money. The greased wheel never rests. The situation is particularly bad in the House, which takes us to our next stop. The middle two defects in the D.C. 4- 3—rigged races and two-year terms—dance with each other like they’ve been dating for a century. And their loony lack of logic will break your heart.

——————–

(To read more about THE PROBLEM, its impact on THE POLICYMAKING, and theUnlock Congress PLATFORM of solutions, read the book! Available for order atwww.unlockcongress.com)