Debates about issues and policies can be boring. Even for journalists. And when you throw in the superficial element of television, plus the competition to draw eyeballs and the imperative to keep them watching, these made-for-broadcast matchups get even further watered down into gladiatorial conflicts. After an unprecedented GOP primary season, the three main events in the general election campaign predictably devolved into the muddiest melodrama we’ve ever seen in presidential politics.

Most of us are so inured to the way these debates go that we don’t stop to think about. But because this melodrama was on full tilt and because the moderators allowed it, or fueled it, not a single serious exchange came to pass between the candidates about an economy that has been transforming before our eyes – and about what steps we should be taking for the longer-term benefit of American workers.

This article is not about Wednesday morning quarterbacking. Let us stipulate that there is not one, single reason why Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton to become President-Elect. While analysts are still poring over data and crunching numbers, it is reasonable to assume that a collection of things, to varying degrees, drove the results, including: Trump and Clinton’s respective peformance/charisma as candidates, campaign strategies, Clinton’s email decisions, Comey’s email decisions, lower Democratic voter turnout, eight years of one party control of the White House, third party efforts and messaging on the big issues.

Of course, on top of that list of issues, as usual, was jobs and the economy. Strategist James Carville’s expression, “it’s the economy, stupid,” didn’t become famous due to its cleverness, but rather from the frequently forgotten power the jobs issue carries. Five months before Election Day, even as I was vehemently opposed to Trump becoming president, I wrote an article about Clinton’s challenges and my fear about his potential route to victory. It included this paragraph:

“Rust Belt states where changing economic realities have been particularly rough on blue-collar, working-class voters could make the difference in this election (and these are the voters who fueled his primary victory). If enough folks buy into Trump’s simplistic yet catchy answers on how he’ll revive the economy, he could have a chance to win in key battlegrounds such as Michigan, Ohio, Iowa, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. He’s a salesman, and it’s a seller’s market. Only say what they want to hear.”

Like many, I certainly didn’t think he’d actually win all of those states, much less the White House. Or maybe I just didn’t want to believe it. While it’s true that the unemployment rate has been cut in half – down to 5% – and more than 14 million jobs have been created since the low point of the Great Recession, to many Americans those are cold statistics. Service sector jobs have been on the rise, but on average pay far less than do manufacturing jobs, which have seen sizable losses. It is pretty close to undeniable that Trump’s message on jobs resonated with many voters hurting in the Rust Belt.

But it’s the complexity of the economic issue that was sadly underdiscussed and underdebated during the 18-month presidential campaign. This is not to confuse it with being under-soundbited. Yes, Hillary Clinton talked about increasing taxes on the wealthy and investing in things like job training and paid family leave. Yes, Donald Trump (and Bernie Sanders) railed on the “establishment” and “dumb” trade deals and Trump threatened companies who were planning to leave the United States. Again, all sound bites. Our transformed economy, which now sits inside an inalterably interconnected world, poses real challenges to the working class. And solving them is going to take a far closer examination than what we heard in the campaign. As President Obama said recently: “It’s easier to make negative attacks and simplistic slogans than complex policies.”

For example, Donald Trump promised to save the coal industry by slashing regulations. Is it that simple? Not according to Michael Webber, who is the deputy director of the Energy Institute at the University of Texas, Austin, and author of Thirst for Power: Energy, Water and Human Survival. Webber points out the number of coal jobs peaked a century ago and that it’s not so easy to go back in time:

“The more recent decline in Appalachian coal employment started in the 1980s during the administration of Ronald Reagan because of the role that automation and mechanization played in replacing miners with machines, especially in mountaintop removal mining. Job losses in Appalachia were compounded by deregulation of the railroads. Freight prices for trains dropped as a result, which meant that Western coal — which is much cleaner and cheaper than Eastern coal — could be sold to markets far away, cutting into the market share of Appalachian mines. These market forces recently drove six publicly traded coal producers into bankruptcy in the span of a year. Mr. Trump cannot reverse these trends.”

Even if you wanted to make that point in a debate, it’s not very well-suited to a sound bite. And no moderator asked, so we also don’t get to consider any counter-point. But a few words in Webber’s assertion, “automation and mechanization,” comprise a common thread in the larger economic question/equation: the role of technology.

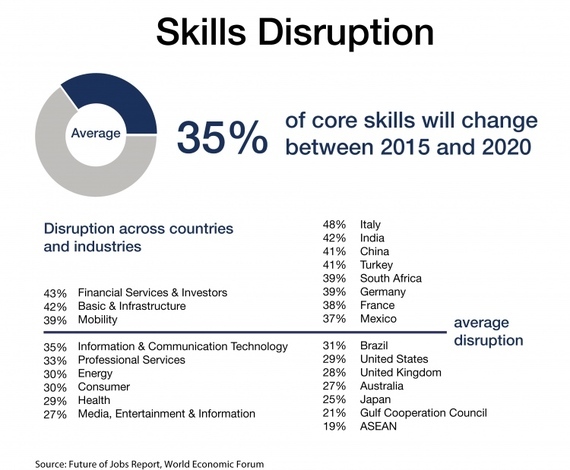

A month before the presidential primary elections this year, the World Economic Forum announced its estimation that a net 5 million jobs will be eliminated by 2020 due to advances in technology. In its report, “The Future Of Jobs,” the WEF surveyed top HR officers and executives across nine industries in the world’s 15 largest economies. The report cites technology as the driving force behind its prediction:

“The Fourth Industrial Revolution, which includes developments in previously disjointed fields such as artificial intelligence and machine-learning, robotics, nanotechnology, 3-D printing, and genetics and biotechnology, will cause widespread disruption not only to business models but also to labour markets…”

We can see these technological forces robbing American jobs in varying numbers in all 50 states. And while we heard zero political debate about this challenge, we did hear plenty of scapegoat-soundbites. And they hit home. The Carrier furnace factory in Indiana, which is cutting more than 1,400 jobs, was a frequent Trump target. In an article filed just days after the election, The New York Times’ Nelson D. Schwartz reported just how much the candidate’s answers mattered to voters in the Upper Midwest. Nicole Hargrove, a Trump supporter who worked at Carrier for more than 10 years, told Schwartz: “If he doesn’t pass that tariff, I will vote the other way next time.”

But would tariffs and a trade war really solve this problem? Or would it negatively impact our exports, and, by extension, lose more manufacturing jobs? We received no substantial candidate exchange on those questions. And beyond the threats of dismantling trade agreements, Schwartz reports that to a great degree, the upshot still comes down to technology:

“Regardless of who is in the Oval Office, manufacturers are seeing relentless pressure, from investors and rival companies, to automate, replacing workers with machines that do not break down or require health benefits and pension plans. Wall Street hedge fund managers are demanding steadily rising earnings from Carrier’s parent, United Technologies, even as growth remains sluggish worldwide.”

It’s not that trade policy isn’t important in trying to improve the economic lives of American workers. It is. So is tax policy. So is the budget. All of the conventional political and policy questions surrounding job creation and rentention are still relevant. But in a country where population has increased to more than 330 million people – in an age where automation is supplanting all kinds of historically human work functions – it seems like the impact of technology is an enormous economic issue that was woefully underdiscussed by both the candidates and most of the media.

I know. Boring stuff. You may now return to regularly scheduled programming.