It wasn’t until my mid-20s that I really adopted any kind of political philosophy or ideology. In fact, it sort of adopted me.

For several years, I’d covered local news for NBC in Fresno. We really reported on the entire San Joaquin Valley — and that included a consistent flow of homicides and violent crimes.

The more I covered crime and the criminal justice system — and the level of poverty in the zones where most of this activity occurred — the more I realized just how interrelated they were. I learned how much these two issues comprised an inter-generational cycle of despair.

In retrospect, pretty obvious. Then again, I grew up in the northern suburbs of Chicago. I did spend much of my adult life living downtown — but never on the South or West Sides. The grittiest parts. The most dangerous parts. The neighborhoods where children literally grow up inside the trauma of a gang economy that sees bullets whizzing by their heads daily. Where kids need a “Safe Passage Program” just to increase the odds of walking all the way to school without getting shot. You may remember an Oscar-winning director making a movie several years ago that takes place in the South Side neighborhood of Englewood. He titled it: Chiraq.

This happens in towns and cities all across America, only on different scales. There is a range of root causes, but what it all boils down to is a lack of opportunity and basic supports necessary for individuals to fulfill their potential.

In 2000, I left journalism and moved back to Chicago to start running political campaigns. I managed center-left Democratic candidates who, like me, wanted to create a more level playing field for Americans who historically and verifiably have not had equal chances. Of course, campaigns have multiple priorities, but this was the one that spoke most to me.

I was soon informed that wanting to achieve this goal made me a “bleeding heart liberal.”

Of course, I was familiar with this term, but I’d never given it much thought before. But the more I heard it — now aimed at me as a pejorative — the sillier I found it. The label seemed not only simplistic, but almost comical: What could be so terrible about having a “heart” that guided one to try to help the underdogs in our country to get a fair shot at working their way toward success?

Obviously, it’s not that simple. Everyone has their own opinion of what’s fair and just. And everyone has to triage economic priorities in their own lives. Strategizing that triage is a big part of what political races are all about. But what is most practical for everyone? Admittedly, that’s a tougher question.

After a few years managing US Senate and congressional campaigns, I was on the verge of winning my first big race. Just a few months before Election Day, a newer friend of mine said he wanted to talk to me about something important. On a Saturday afternoon during the summer of 2006, I sat in David Scherer’s kitchen and listened to his pitch. It was about helping under-resourced, under-prepared community college students in Chicago to get their associates degrees — and launch successful careers.

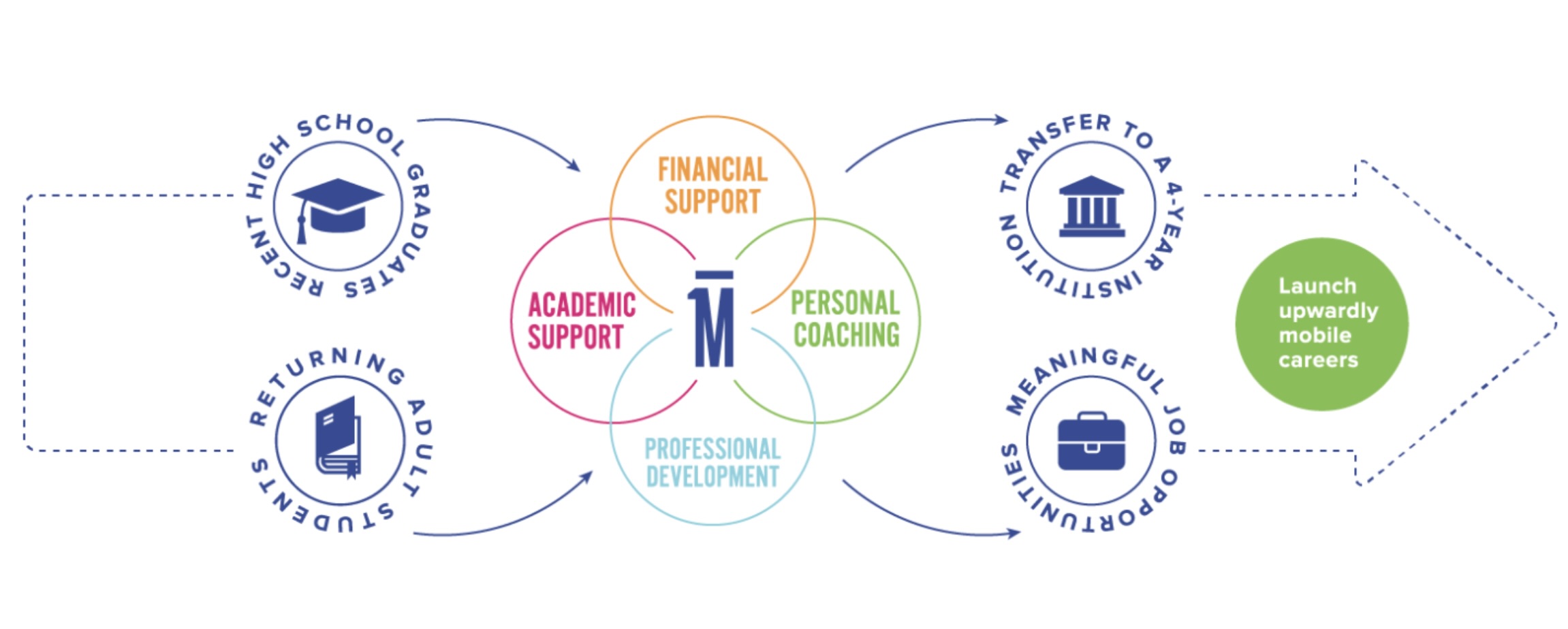

David wanted me to help him to expand a nascent, private program that he and others had founded inside the City Colleges of Chicago. The DMK Jr. Foundation was funding about 20 students at that point, but with a unique, 360-degree scholarship model: In addition to the last-dollar “gap funding” that students were provided, they were also afforded support in the form of academic advising, tutoring, and mentoring from volunteer coaches.

David wanted to reincorporate DMK and blow it up into a public/private partnership that would eventually serve exponentially more students. There was one sentence he spoke to me that day that I will never forget:

“Michael, 63 percent of the college students in Illinois are enrolled in community college, and only 1 in 3 complete their two-year associate degree within three years — and nobody’s helping them.”

I was skeptical. If this was true, it would be a colossal waste of both taxpayer money and human potential.

It was true.

Anyone who knows me knows that I’d never describe myself as particularly “smart” (more on what “smart” really means in an upcoming column). But David is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. I didn’t know his politics in ’06, and it didn’t matter. His solution seemed pragmatic. And necessary. And effective. In other words — smart. And he said he wanted me to partner with him because I’d bring political contacts, media contacts, business contacts, and I knew how to lobby. He was right about the first three. I figured out the fourth.

But the very first thing I did was to start assembling a new Advisory Board with big name elected officials — from both sides of the aisle. And I would not allow the program (now known as One Million Degrees) to be cast as some “liberal handout” — because it wasn’t. When I walked into the offices of these powerful business leaders and officeholders, my passionate pitch was always the same — regardless of their politics:

“Listen, these students and these community colleges are the most underused economic and human resource in Chicago. They are mostly first-generation college students who are working their asses off at one of the City Colleges — but they are failing out at a staggering rate. Over 65%. And it’s costing us a ton. These students receive MAP monetary assistance from the state as well as federal PELL dollars. Wasted. Same as their individual potential…

“But on top of that, we NEED these students to graduate and help us to fill the critical skills shortages in our city and state! Associate degrees are potential gold for our local economy. And the brutal fact is that for most of these students who do fall off the tracks at this late educational stage — the odds exponentially increase that they will need to depend far more heavily on social entitlements funded by our tax dollars. For a long time. Or worse. We gotta help these kids! They don’t want a ‘handout.’ They just need a leg up to make the hard work they’re already doing pay off. That’s what this program does. Successfully. Our students are succeeding. It’s win-win-win.”

No one argued the point. If they had any objection, it was that they thought a similar type of support model should exist in K-12 education. We agreed — but one thing at a time.

The strategy proved effective: three Democratic and three Republican U.S. Representatives from Illinois immediately joined our Advisory Board. Two successive Democratic Governors gave us their names and support, as did an influential Chicago businessman who’d run for the same office as a Republican. And it took less than 20 minutes on a single conference call to get the Republican House Leader to officially join the cause.

When I first presented our program in front of the Illinois House Higher Education Appropriations Committee, it was nearly the same pitch (perhaps a little louder). I asked why they would go on wasting millions, when they could be helping us build a program that could save them millions. They started funding us at a low level: $250,000. And we were grateful. At that time, that grant was 20% of our annual budget.

But the real public/private partnership we sought was with the City Colleges of Chicago. We were already friendly; they’d given us free office space since OMD’s inception in their administration building. But that was the extent of it.

Over the years, the number of students OMD served grew from the original two dozen to more than 2,000. And under David’s leadership as board chair, an extraordinary staff made continuous efforts to measure and improve the program. And it worked.

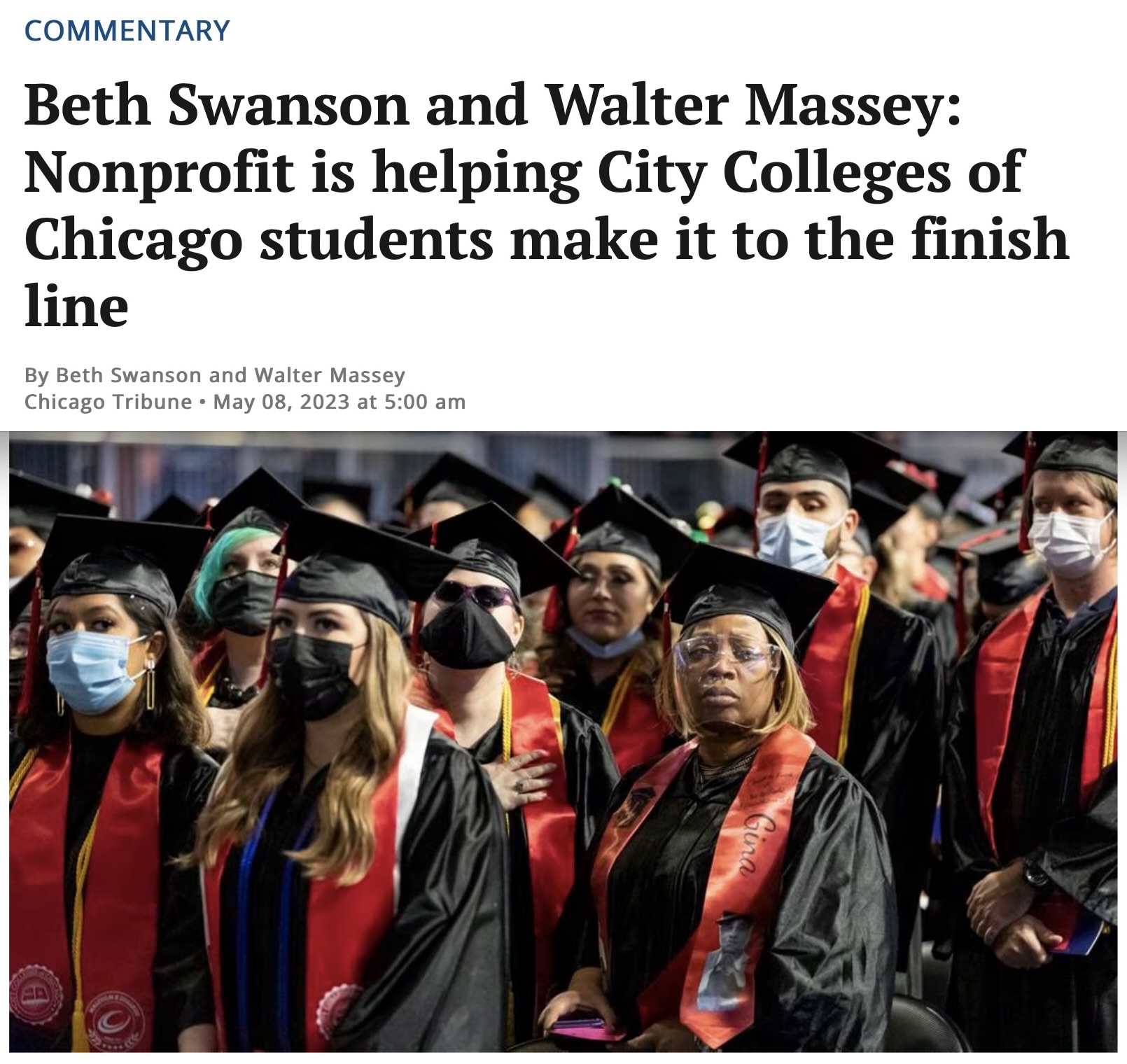

Just days ago, the Chicago Tribune featured a commentary trumpeting a new “four-year plan to embed OMD’s services throughout the City Colleges system and begin to transition to public funding. Under this partnership, thousands of City Colleges students will automatically be enrolled in the OMD program, giving them access to professional and academic coaching and financial support.”

This is the type of impact that we were after all along. And the authors of the commentary, Beth Swanson, CEO of A Better Chicago, and Walter Massey, Chair of the City Colleges Board of Trustees, cited data from an ongoing University of Chicago study that is already confirming the efficacy of the OMD model.

Liberal Schmiberal. Conservative Fluburvative. When it comes to America’s toughest challenges and how to solve them, we must do everything we can to find the most effective solutions possible. Then scale them.

That’s smart.

On Friday, May 19, One Million Degrees will host its 16th Annual “Degrees of Impact” Gala in Chicago. To contribute or to volunteer as an OMD coach, please visit our website.