Mastering the art of storytelling to drive change.

Michael Golden created The Golden Mean as a place to share his passion for storytelling and to connect with purpose-driven partners who want to master the art of strategic communications.

“The Golden Mean” is more than a curious phrase that includes Michael’s surname; it is an age-old principle which holds that virtue lies between the extremes. If a person can travel the middle path of moderation and temperance in life, goodness and beauty show up along the way.

Applying The Golden Mean to daily life is a practice that Michael is always trying to master — or at least remain conscious of. In other words, it is an aspirational concept. The genesis of Michael’s perspective started a few years back. Here is his story…

December 3, 2019

It was on a Sunday in July a few years ago that I came to the realization — self-admission — that I’d been abusing drugs and alcohol for several years. It wasn’t that I had a physical addiction to any one thing; I just used to throw it all together. Opioids, Benzos, weed, booze, whatever. I was aware at the time that on any given morning, it was possible that I might not wake up. I didn’t care.

The daily pill-popping was something I had rationalized for about five years. The story I’d told myself was loaded with the usual cliches (“highly-functioning, loves to have fun, not addicted…”). But the deeper truth was that I was in thrall to excess. To the extremes.

If that sounds bleak, flash forward about six months — when the real bottom dropped out.

As I lay paralyzed in a darkened bedroom, I finally understood just how debilitating a disease acute depression is for so many. I felt like an inmate and a guard at the same time. My body hurt all over, though I’d suffered no physical injury. For the first time in my life, I had to be persuaded to eat.

The irony was that I hadn’t touched a single substance during those intervening six months. I’d started hiking the Sonoran Mountains, gotten into shape and threw myself into a new teaching position at ASU. I genuinely thought things were going pretty well.

Yet there I was, glued to a bed in daytime darkness, hour after hour, wondering how I would ever get the pain to stop. I remember thinking that jumping in front of a bus wasn’t something that I could ever actually do. But I also remember thinking that if the bus could just find me and take care of business, my problem would be solved. And that would be that.

Somewhere in between this cascade of negative thoughts, I wondered to myself how could this have happened. Just a year earlier I’d celebrated a big birthday in grand fashion — an awesome bash full of love and laughs with my favorite people in the world. Now I couldn’t even understand why they’d shown up. How could a dive this steep come this fast — seemingly out of nowhere?

As I learned, this months-long period of depression was far from random. And the substance abuse wasn’t the core problem. A confluence of things had been quietly building up inside me for years. It all manifested itself in chronic and scathing self-criticism — imposter syndrome. Being in that hole was the real thing driving all the destructive behavior.

My dearest ones scraped me up off the canvas and pointed me back in the right direction. They were incredible. But the rest was up to me.

Since crashing into that bottom, I’ve taken some of the usual steps you might expect: therapy, medication, hard talks with family, and maybe most importantly, just getting up every day and trying.

The journey back is an uneven one, to be sure. But along the path, I discovered a guiding principle that’s turned out to be something of a salvation. I’ll explain why and how, after defining it.

The Golden Mean wasn’t a new concept to me. In fact, a while back I’d made it the title of my podcast. The theme of traveling a “middle path” seemed like the perfect metaphor for the common-sense conversations I wanted to share. It also symbolized the values of pragmatism and compromise that underpinned the book I’d written about repairing our defective American government.

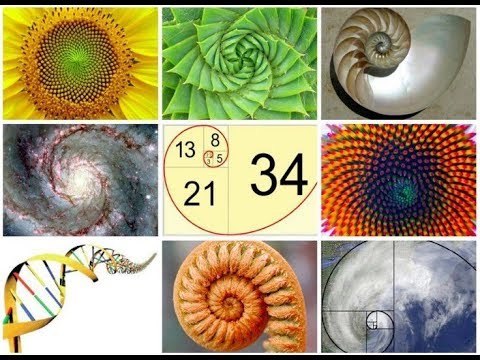

Although The Golden Mean is a philosophical principle, its origins are rooted in mathematics. The unique number known as “Phi” — 1.618 — represents a “Golden Ratio” that can be found in art, theology, cosmology, nature, architecture — even financial markets.

Phi is derived by dividing a line so that the longer section divided by the shorter is equal to the full length of the line divided by the longer. If the verbal description sounds a bit confusing, here’s what Phi looks like when it’s geometrically reduced down several times into what are known as Golden Rectangles.

The Golden Ratio has gone by many names through the ages: The Divine Proportion, The Golden Section, Medial Section and Golden Cut. Its visual representation shows up again and again in the world that surrounds us, from the architecture of The Great Pyramids to the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci to the Fibonacci Sequence that we see in nature and the galaxies.

At some point, the great thinkers of the ages started converting the mathematical Golden Mean into the philosophical. Its definition varied a bit from discipline to discipline, but the essence was always the same: Stay away from the extremes. Find the middle track. Out of moderation, comes virtues. Truth. Beauty. Balance.

In Buddhism, it was known as The Middle Way. Confucianists called it The Doctrine of the Mean. But in about 350 B.C. the Greeks — Aristotle most famously — elevated The Golden Mean into the contemporary concept we talk about today. The Mean was so essential to Greek philosophy that they inscribed it on the Temple of the Apollo at Delphi: μηδὲν ἄγαν μηδὲν ἄγαν — “nothing in excess.”

That word — “excess” — describes the state I operated in for far too long. No matter what the activity or goal was, if I pursued it, the entirety of my focus was on the result. The faster the better.

Of course, going after what you want in life is not in and of itself a vice. Nor is fierce competition. But the reasons driving the intensity of the approach matter — and mine were backward.

As it turned out, I was trying to fill a pretty big void. My excessive self-criticism came from a dark place internally — and it drove so much of my extreme behavior externally. All I wanted to do was prove myself. Again and again. To myself and everyone else. But even when I achieved “success” — it never filled that empty box. It was also bloody exhausting.

People who know what it’s like to constantly feel damaged in some way also know that it becomes a vicious cycle. It builds and builds until the bottleneck can hold no more.

A pressure cooker was camped out inside my head, and it led to the real vices. We all have them. Mine went viral.

Not just drugs and alcohol. Any superficial activity that made me feel good. I’d say the best example of this was the way I used to throw dice in a casino. So many hours of my playing happened at a player-less table at 3am — just so the rolls would come faster. I wanted more. In retrospect, a pretty silly use of time.

My extreme approach bled over into relationships, too. When you fall too hard and too fast — and then keep the pedal to the floor — no one has room to come up for air. I didn’t care. I just wanted more.

Little did I know when I reached that bottom that it would ultimately serve as a springboard.

A dear friend of mine, who was instrumental in helping me to survive the depths of that downward spiral, is fond of saying: “Your strengths are your weaknesses.” This resonates with me beyond description.

I love people deeply and I also deeply care about the things in this world that I find cruel or unfair. And my M.O. is to take an active approach to all of it. That’s the good part. But when I do, if I’m not trying to balance the passionate heart with the practical mind, I’ll never get to the place I really want to go.

The place I live in now has little to do with winning or status or profile or any of that fleeting stuff that doesn’t have much meaning at the end of the day. Now, as best I can, I travel along that middle path, connecting with people while staying in the moment. It’s as old a goal as humanity itself. Yet without having any awareness around it, you can never really be in it.

Most of the time, figuring out how to exist in this world is not really all that complicated. So often, we make it complicated. I did that for a long time. Excessively.

The Golden Mean doesn’t require the sidelining of personal passion, nor does it outlaw the thrill and celebration of love and accomplishment. Or even frivolous pleasures, in moderation. All it does is remind one not to be mastered or drowned by any of it — by anything in the extreme. Good or bad.

All of this is not to say that it’s always easy to ride the Mean. Like any worthwhile endeavor, it’s a practice. But even when I find myself getting pulled toward the extremes, or feel an aftershock of the darkness, I take note, let myself off the hook, and then find my way back to the center.

That’s the place where I can feel my strengths the most. It’s where I can acknowledge the full measure of my talents and choose the most worthy efforts to channel them into. When I have this mindset on, I’m not confused at all about why those amazing people keep hangin’ around my life — no matter what. For this, and for them, I am so very grateful.

By sharing this story, it may sound a bit like I’m preaching The Golden Mean. But I’m not the preachy type. If any part of my experience resonates with one person in pain, of course that would be wonderful.

What I’m really doing is talking to myself — keeping that guiding philosophy front and center. For it gave me solace. It freed me.