I felt like I was losing my mind. Literally. My brain raced round and round in a loop of hyper-anxiety. Like a Formula One car at Indy — but with the wheel and pedal being operated via remote control.

If the state of mind I’ve just described sounds scary, that’s because it is.

The twin demons of depression and anxiety had visited me to this degree only once before. It happened about four years ago and it came as a total shock. I coped with it through a months-long process of identifying the personal roots of it and by starting medications. The latter I did reluctantly. But they worked.

So in the summer of 2021, when this second acute episode gripped me, not only was I surprised, but deeply disappointed: Hadn’t I already conquered this condition? Sure, there had been minor setbacks along the way back, but nothing serious. So even though I could tell that my propensity for self-flagellation was flaring up again, why had it plunged the rest of me so far back down?

Beyond the negative thoughts that kept cycling through my brain, even more unnerving was the intense anxiety that I just couldn’t shake. All of a sudden, basic tasks seemed intimidating to complete. It was almost paralyzing.

I must confess that even when my mind is humming along just fine, I experience flashes where I wonder whether the external reality I’m perceiving is a true reality. Often I see things in this world that seem just too cruel or stupid to be true. This includes the torture that some of us inflict on ourselves. On some level, we know it’s unnecessary, that it lacks any logic. Yet we still do it.

When my mind goes into a full tailspin like it did last July, it can make me feel like I am unwittingly caught up in some manufactured tableau — an unreality — and everyone is in on the joke except me.

I’m fully aware of how detached this sounds. Yet I also know that I’m not the only one who entertains the thought. You may have watched The Truman Show. Or The Matrix. Or Groundhog Day. Or Westworld. Or Stranger Than Fiction. Or A Beautiful Mind. Or Inception. Or Vanilla Sky. Pick your flick — they were all born in the human mind. How many other people have these thoughts and just never put them down on paper?

I talk about this stuff sometimes with a psychiatrist named Mark whom I’ve seen on and off for several years. We usually have a good laugh about it. But last summer I wasn’t laughing.

As I conveyed my fears and anxiety to Mark, he didn’t seem alarmed. I told him that I dreaded having to go deep again to lift my psyche out of the cellar. But he disagreed on the cure:

“Michael, I think you already figured all that stuff out. I’m pretty sure this is mostly biological — we know it runs in your family. I think that when you are not on one of those medications and you’re plummeting, there is no floor to allow your mind to get back to level. I’m pretty confident that if you start the serotonin again, you will be thinking and feeling like yourself in a couple of weeks.”

It had been more than a year since I went off one of the medications Mark had originally prescribed. I didn’t like the side effects. And I had been hoping to halt the other med right about this time — I just didn’t want any of it in my body anymore. But he quickly dissuaded me from that idea.

I told Mark that I desperately hoped he was right, and to call in the scrip. But at that moment, I was actually more concerned about getting through the hours that lay immediately ahead of me. My mind was still in that cage where I just couldn’t change the channel: a feedback loop of negativity. I live alone, and when you’re in this state with no one around, time can stretch out like a galaxy.

Mark knew exactly what I was talking about, and the short-term solution was pretty simple: Be around people. Especially the ones who care about you most.

When I first experienced this form of darkness several years ago, I was reticent to share it with too many people. There’s a shame and embarrassment that can come with depression. There shouldn’t be, but there is.

While all of this was happening in to me in 2021, I was watching world-class athletes like Naomi Osaka, Michael Phelps and Simone Biles talk very publicly about their mental health challenges. Each spoke about the fact that they needed some form of help. Osaka had just done a Time magazine cover that was bannered with her quote: “IT’S O.K. TO NOT BE O.K.”

Nobody wants to remove themselves from the activities and events that they ordinarily enjoy. None of us want to waste the limited amount of time we have left on this planet suffering through pain and mental anguish. But it can happen to anyone. Our emotions are largely driven by our thoughts. And when you have lost the power to control your thoughts, that’s the time when reaching out to others makes the most sense.

Howie Mandel was one of my favorite comics growing up. Not long ago, I came across his perfect articulation of this principle:

“There isn’t anybody out there who doesn’t have a mental health issue, whether it’s depression, anxiety, or how to cope with relationships. Having OCD is not an embarrassment anymore – for me. Just know that there is help and your life could be better if you go out and seek the help.”

I realized that I was in that place, so this time I called in more reinforcements. I told my friends about the grisly drama that was repeating itself over and over in my head. On short notice, I grudgingly asked a few of them to pay me a visit — just to break up the isolation. They were there in a snap. And their company and empathy did help me get through some of the early hours.

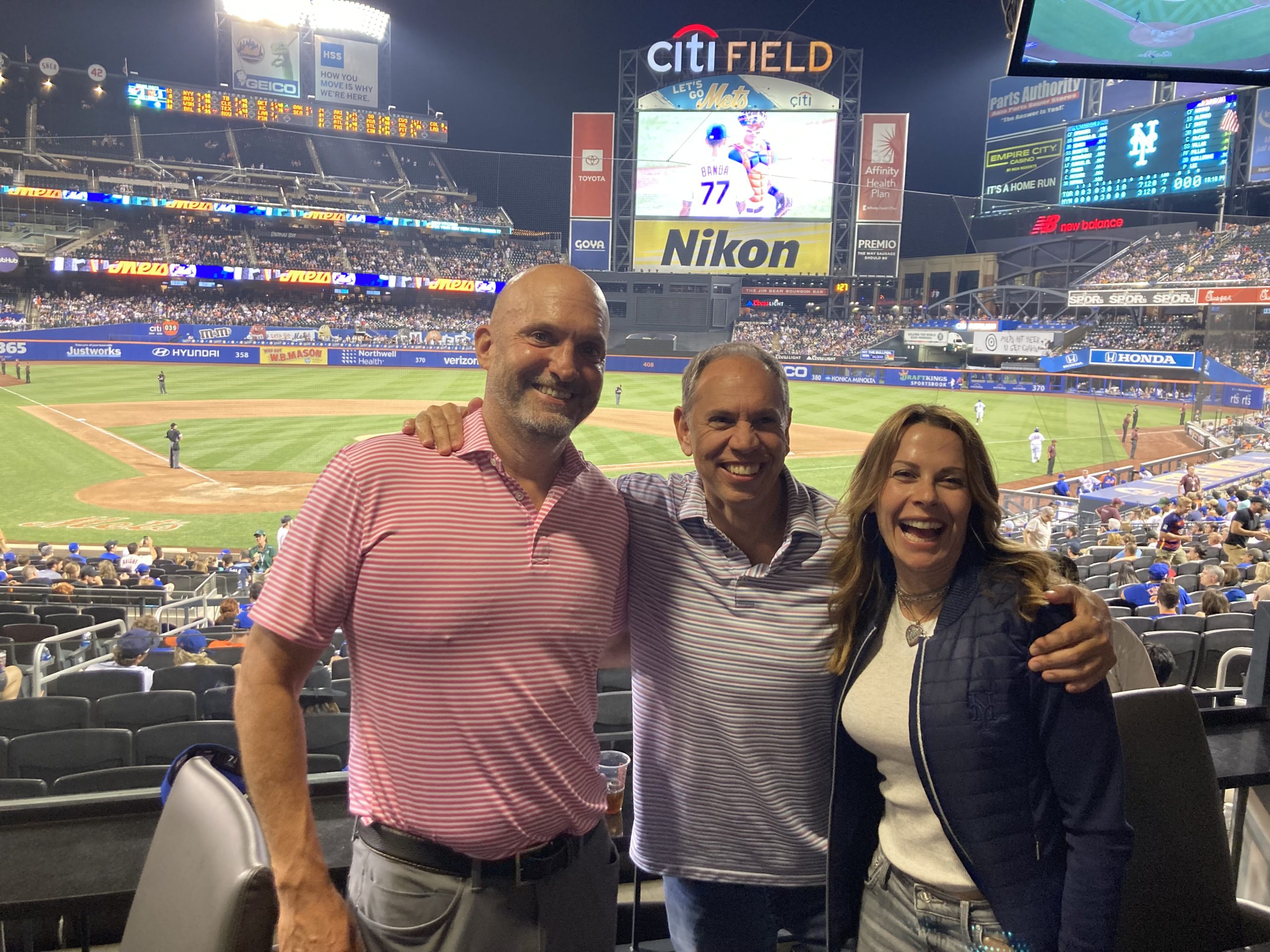

But a few days into the episode, I was still in bad shape. I called two of my dearest friends, Brian and Karen Cohn, who live in Greenwich, Connecticut. I was already scheduled to visit them and their kids the following week, as is our summer custom. But when I told them what was going on, they took it upon themselves to change my ticket and persuaded me to fly in the next day.

I hated the thought of Brian and Karen having to see me in such a deeply depressed and neurotic condition. But on some level, I knew it was the right thing to do.

For more than a week, as I waited (and hoped) for the new medication to take effect, my Cohn family helped me to slowly regain my strength.

Naturally, they disavowed me of there being any validity to the scathing self-judgments I was soaking in — as had my other friends. But that doesn’t always break through right away, if at all.

There is a ton of discussion these days about the value of self-compassion when it comes to mental health. Rightly so. Believe me.

But far less talked about is the ability to receive compassion from others. For many, this is not always so easy — even if there’s a part of us that craves it. Yet for those who suffer from acute depression, being able to absorb compassion from others is an essential ingredient to mitigating and recovering from the condition.

In 2016, scholars from seven Canadian universities conducted a cross-cultural study on this specific question. The group began with the predicate, borne out in prior research, that excessive self-criticism is a concrete personality trait that has a direct correlation to depression. Fairly obvious.

But what the researchers discovered was that depressives who suffer from this thought process can temper their condition if they can allow for compassion:

“Being open and receptive to care, warmth, and kindness from others may buffer the depressogenic effect of self-criticism, while being uncomfortable or fearful of compassion from others exacerbates this effect.”

The way we see ourselves is always a balancing act. No matter how emotionally secure a person is or how practiced they are at taking their mind’s focus away from the “egoic” self, it is nearly impossible to escape caring about external evaluations. Even the Buddha would affirm that being concerned about how we’re perceived in the world around us is a totally human characteristic. The key is to never become reliant on these perceptions. In the spirit of “The Golden Mean,” it is about staying away from the extremes.

Maintaining this kind of balance has always been a challenge for me. And there is no question that my friends’ words of compassion have a moderating effect when my mind is involuntarily digging a hole in which to bury my self-esteem.

But I think the other way that Brian and Karen helped me during that visit was through the compassion they showed me just by having me there. By listening. By joking. By doing the normal things. Watching the kids play sports. Going to a ball game. Ribbing me about the usual stuff. Eating dinner with the family. My friends helped me by making me feel like I still belonged. This may sound silly, but if you’re lost, it’s huge.

In retrospect, thinking about the mode my mind was in at that time, I probably needed for them to see me in that condition — and still want me there. I trust that they did, since they invited me back out a month later.

Mark turned out to be right about the effectiveness of the meds: Two weeks later, my rational mind returned (relatively speaking). It was an indescribable relief. I was back to laughing, working, writing and playing golf. I’m not creating any illusions here — it wasn’t like I was skipping down a yellow brick road whistling Sinatra. But I felt better. I felt human. I felt more like me — the real consciousness that sits behind that constantly carping voice in my head.

I also learned a lesson. There are millions of people, be it through nature, nurture or both, who have mental health challenges that do not always have cookie-cutter answers or one-time fixes. Pathways to recovery can come in spurts and through a range of actions. And sometimes when people are trapped in these states of mind, receiving gestures of love and compassion is not something to fear or resist. On the contrary, it can be the very bridge that connects a person with the rest of their solution.

I’m grateful for my people, for their generosity and compassion. And I know far better now the true value of being able to receive it.

God forbid you ever find yourself in a similarly uncontrollable state of mind. But life is pretty unpredictable. If it ever smacks you in the face like it did me — and all of a sudden you can’t find the wheel — the best thing you can do is to let people in. They want to help, and their power to help restore the real you is immeasurable.