When John Lindsay first saw the looters heading toward his New Breed Furniture shop in uptown Kenosha, he hadn’t yet boarded up his business. So he got right out in front of them.

“They ran up to my building and they grabbed my dumpster and they threw it in the street. Then they started running up to the main window, and I just got in front of it and I begged ‘em. I told them: ‘I’m a furniture maker. I’m an artist. I hire locally.’ I begged them not to do anything, and they apologized. Then they put my dumpster back and then they went off to do harm to others.”

John was the first person I spoke to after arriving in Kenosha on a Tuesday morning. It was a week after the city had been rocked by riots stemming from the police shooting of Jacob Blake. It was also the day that the president was coming to Kenosha, amid public calls for him not to.

I had driven up from Chicago more or less spontaneously. Having watched from afar what was happening to our neighbors to the North, Kenosha seemed like a community both hurt and angry — but not just about a single police action. Like so many cities across the country that have seen overwhelmingly peaceful protests, Kenosha was dealing with the painful aftermath created by a relatively small group of rogue actors who’d been committing costly acts of violence.

John Lindsay was describing the second night of the protests when arsonists set fire to more than 35 structures. A blaze along 60th Street, right near his shop, nearly leveled the three blocks between 11th and 14th Avenue.

“I just received a $40,000 lumber order on Wednesday, and now there are arsonists everywhere… They weren’t from around here. There were no local people at all —100 percent from out of state or out of this area. A lot of people from Milwaukee, I believe. And Chicago.”

The next night, just a few blocks away, 26-year-old Jessica Kwic was watching a livestream of the counter-violence that had started right outside her house. At around 11:00 pm, she says she got into bed and started reading — hoping it would help her nod off. But Jessica was wide awake when she heard the sound just before midnight.

“Suddenly I heard about a dozen shots ring out and I heard screaming. I ran to the window and saw about three to four people running up the street. I was so scared. Their faces are burned into my memory. Same with the sounds of the screams and gunshots. I spent the next day in tears because I couldn’t stop hearing it all, especially after I found out what happened.”

Three people were shot. Two of them died. Anthony Huber and Joseph Rosenbaum were both from Kenosha.

The gunman was a 17-year-old from Illinois toting an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle. He and a group of others had arbitrarily deputized themselves as the protectors of vulnerable Kenoshans under threat from the rioters. Jessica says they made it worse.

“It’s totally unacceptable. He had no reason to be here. And I truly believe that if they weren’t here, that that would not have happened.”

John agrees. But he’s angry at both sides. The father of an autistic son, he moved to Wisconsin 14 years ago for its special education programming. A white business owner with a sign tacked to his storefront that reads “Black Live Matter – A Lot” — he says he still supports BLM. But he is furious about the extremists who lit the match on an already explosive situation.

“I believe both sides are woefully immature. They’re wrong, deeply wrong. These people aren’t adults. They’re acting like children, and they’ve dragged down what is one of the most beautiful Midwestern cities. They’re all unwanted tourists that came and performed horrible violence to this community. They burned down the place that the kids around here go for their ice cream, their tacos, their food. It’s been nothing but pain and sorrow for the Black families in this neighborhood.”

While John and I are talking, tempers are running hot just a few feet away. A crowd has gathered outside the gas station on the corner of 60th Street and 22nd Avenue — just a few blocks from where the rioters had done their worst. Kenosha Police have the intersection roped off in anticipation of the presidential motorcade.

Two gawkers shouting the loudest — at each other — are Megan Donovan and Anthony Davis. I jump in the middle and ask them if I might moderate for a minute.

Anthony, an African-American who’s driven down to Kenosha from a town two hours north, is wearing sweats, flip flops, a BLM baseball cap, and a black t-shirt describing Donald Trump as a “dumb mother-fucker.”

Megan, a white woman from Cicero, Illinois, is sporting black boots, a military camouflage-colored cap, and an “LGBT” t-shirt that reads “Liberty, Guns, Beer, Trump” under the acronym. She’s carrying two big flags with her, one the stars and stripes and another with a custom message: “All Aboard The Trump Train.”

Anthony blames Trump for the current climate in our country. He points at Megan and cuts right to it.

“Trump is a racist. He’s a bigot. He’s a rapist. He’s a child molester. And he’s a conman.”

Megan responds that Trump is better than all the “lifer politicians who’ve been lying to us over and over again.”

I ask Megan what she thinks of the protesters who marched peacefully; the ones not doing any damage.

“I feel like the Democratic party, the Black Lives Matter and Antifa are all infiltrated by an outside group of fascist elites, who are from the old Nazi Party.”

It’s a tired old argument. But the vitriol is visceral. And it’s not their city.

As I walk a few blocks south onto 63rd Street, I see the rubble that used to be the Danish Brotherhood Lodge. Founded in 1884, the historic club is one of the civic anchors of the community. In a matter of hours, rioters burnt it to the ground.

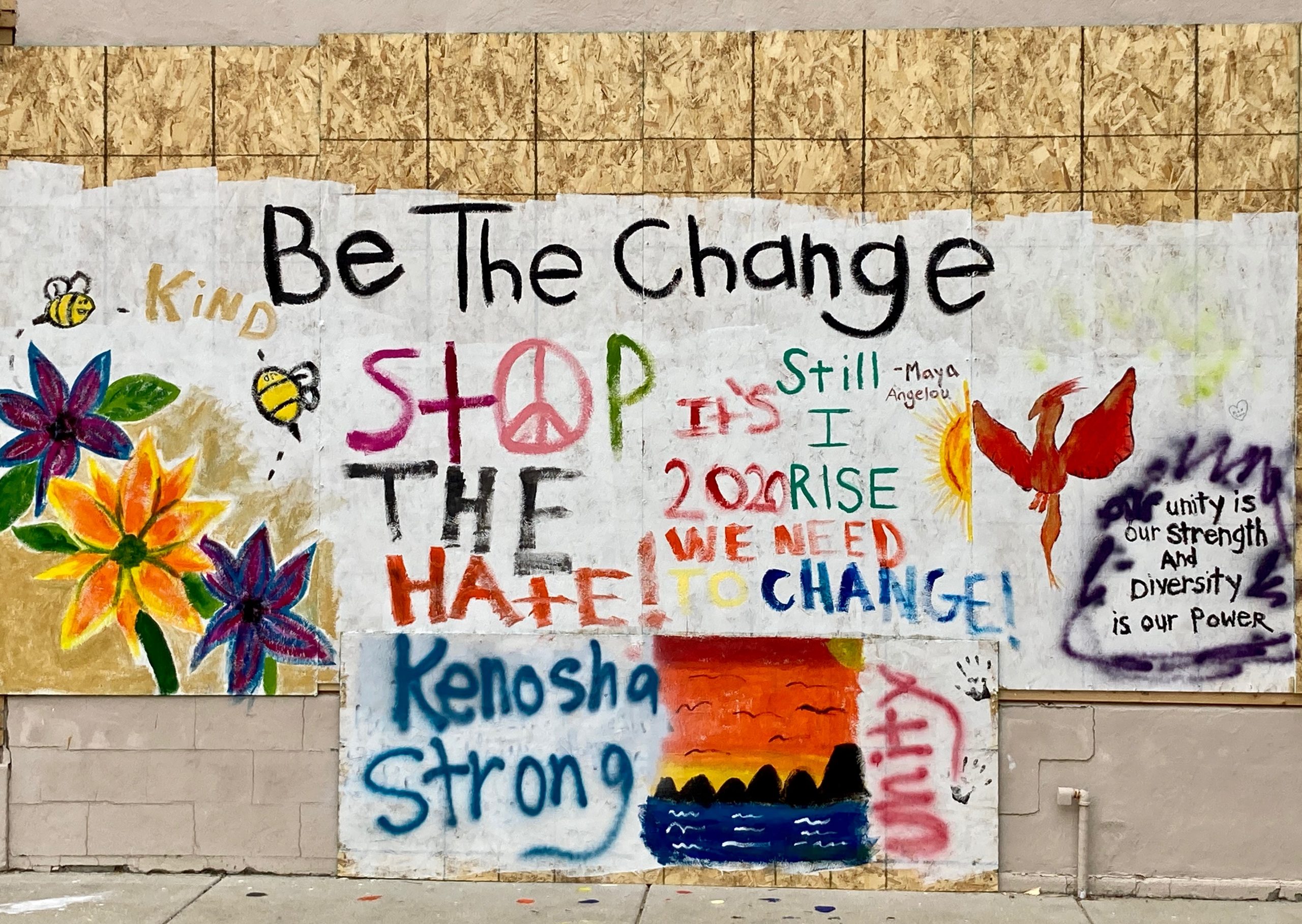

Across the street, I meet the owner of the Faded Barbershop For Men, Tricia Betancourt. Her business was somehow spared, and like many others that survived, its storefront is now guarded by artistically decorated wooden boarding.

Tricia knows that she and her partner lucked out. But she’s still plenty worried about what comes next for Kenosha’s uptown.

“It was pretty devastating. We were blessed. Our building didn’t get hit. But we still have the effects of our whole area being demolished. What happens in this area now? Because we don’t want to lose that diversity. You want to keep it what it is, a hard-working small business area.”

Half a block away, where 63rd Street meets 23rd Avenue, I meet Carlos Del Toro. During the rioting, he’d hunkered down in his apartment. He made it through those three nights safely, but he doesn’t feel safe.

“It’s scary now to be here. At night, I don’t even want to come outside, ’cause I notice that a lot of people are walking around with guns and everything…What happened — those people are not from here.”

I see some of those people still protesting just a few miles away at the Kenosha County Courthouse. This is right about the same time Donald Trump is starting a private event 15 blocks north at Mary Bradford High School.

The courthouse scene has calmed considerably since the night prior when protestors tried to push over the protective metal barricades. But they are still yelling at the Wisconsin National Guard Troops stationed on the inside of the courthouse complex.

Among the protestors is Chris Bee, a young LatinX from Grand Rapids, Michigan, who’s decided to spend his 20th birthday in Kenosha. He looks the part, megaphone in hand, t-shirt announcing “FUCK POLICE BRUTALITY,” a Black Lives Matter baseball cap and matching black flag slung over his shoulder.

Chris says he thinks that America’s progress has been far too incremental over the 50+ years since the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Right Acts. He believes police misconduct prevents minorities from being able to actually exercise those rights.

Chris conveys his point of view to me in a pretty measured fashion. But when I ask him if he condemns all of the violence committed by the irresponsible few on the first night of the protests, his answer is a sidestep.

“As a person of color, but not a Black person, it’s not my place to tell Black people and African-Americans how to protest. How they protest is how they protest. It’s not my place to tell them how.”

And therein lies part of the rub that is vexing cities across America.

Tens of thousands of Americans are protesting abuses suffered by minorities at the hands of the police. Rightly so.

At the same time, a relatively small number of people are wreaking the kind of havoc that hurts individuals, damages communities and detracts from the message. Then various BLM supporters — sometimes public leaders — signal their tacit approval.

This support give extremists on the other side what they think ia an excuse to take drastic measures of their own to “help” — even when law enforcement officials make public calls for them not to do so.

On August 30, six days after the first protest, the Kenosha Police Department reported that of the 175 people arrested, 102 of them were not Kenosha residents. Most of those arrests were minor charges for curfew violations.

Of the five people charged with felony burglary connected to the looting, two are from Kenosha and the others are from three Wisconsin cities: Janesville, Madison, and Racine. Investigators are searching for the arsonists and have identified nearly a dozen persons of interest.

The shooter from Illinois faces multiple charges, including first-degree intentional homicide.

But whether the perpetrators of these crimes are locals or outside intruders, it’s their actions that are the real issue. These events often become a vicious cycle where everyone loses.

In many cities, law enforcement departments have made substantial efforts to navigate and protect peaceful demonstrations — where marchers are protesting their policing. But when the violence starts, cops’ jobs become even tougher. And that’s before vigilantes like the Kenosha shooter come into town with long guns and short tempers. They often add to the trouble — and then try to justify it by referencing the original violence.

In the days and weeks following many of these events, dueling interpretations and recriminations start to play out. Some of these disputes get settled later on in courtrooms. But that doesn’t change the realities on the ground for the communities that are left to pick up the pieces of the chaos and destruction.

Tricia Betancourt loves her city. She loves the people who come into her barbershop to get their hair styled. She loves the diversity of her clientele, and the friendly conversations they have every day sitting in her chairs.

What she dislikes is when her town gets caught in the crossfire. Even as she knows that she and her neighbors must continue to stand up and defend what’s just.

“I have Black family, and I don’t want to keep this train going. This city needs changes and this country needs changes. I hope this brings light to a lot of people that this is a real situation. We don’t want to focus on the riots and we don’t want to focus on the window-bashing…There are injustices happening in our community and across the country. So we want to remember what this is all about, and that is Black lives mattering.”

John Lindsay didn’t just approach the protestors who were assaulting Kenosha and threatening to damage his furniture shop on that first night. One night later, he walked right up to the self-appointed protectors holding long guns and tried to persuade them to stand down. He tried to explain that no matter who’s bringing violence into the equation, all of it just ends up inflicting pain on his community.

“Looters are losers. Arsonists are assholes. Shooters are shitheads. So whether you’re the white militia or you’re the activists that believe that violence is somehow helpful…the ends never justify the means.”

Kenosha has already started to rise from its ashes. Literally. Folks are raising money and helping each other to survive and begin rebuilding. They’re staging the kind of comeback that so many other communities have been forced to mount in recent months.

Meeting with Kenoshans and hearing about the trauma they’re been experiencing was heartbreaking and inspiring at the very same time.

It was also a stark reminder of how the violent acts of a few can tarnish the righteous efforts of so many.

It is America, in 2020.